|

| Bedspread, English roller-printed chintz, ca. 1820 |

The bedspread currently on the bed is one that, as far as I can tell, has never been displayed before. It is made of a single layer of cotton chintz printed in a pattern that combines a variety of floral motifs in brown, pinks, blue, and green. The material is only twenty-six inches wide, and the lengths are sewn together with very narrow seams of less than a quarter inch. The top hem is faced with a strip of cotton in another print. The material was most likely made in England around 1820 using the roller-printing process.

|

| An example of an Indian chintz made for the European market, ca. 1750-1775 |

|

| Block printer at work. “Calico” was another general term for a printed textile. |

In the 1750s, copperplate printing was introduced in Ireland. This form of printing fabric uses the same principles as printing on paper—a metal plate is engraved with the design and ink (or dye) is applied to the plate. Copperplate printing had some advantages over block printing: patterns could be much bigger (because the printing was done with a press in which the fabric was laid on top of the plate) and images could be much more detailed and realistic. Copperplate printing was used to produce the famous toiles de jouy, but was also used for chintzes.

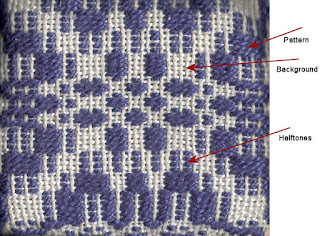

A major revolution in printed textiles came at the end of the 18th century with the invention of roller printing. This uses an engraved plate fixed to a continuously rolling cylinder, which is refreshed with new coloring medium on each turn and prints the fabric in one pass from end to end. Roller printing eliminated the need to reposition the block or plate, as well as the fabric, after each impression. The advantages were immediately apparent—printing was much faster and thus, cheaper. For the first time, printed textiles could be produced on a large scale. This, combined with new developments in chemical dyes, meant that by the 1830s, they were no longer luxury goods exclusively for the middle and upper class, but were widely available (they lost much of their prestige among the well-to-do at this point—hence the term “chintzy” for something cheap or gaudy).

|

| Detail of bedspread. Note that the pattern runs all the way to the selvedge. |

As is unfortunately the case with many of the items in the collection, we don’t know how Alice acquired this bedspread or what its history might be. But it certainly makes a fine addition to the Sheraton Room!

Sources:

Printed Textiles 1760-1860 in the Collection of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum (Smithsonian Institution, 1987).

Eileen Jahnke Trestain, Dating Fabrics: A Color Guide, 1800-1960 (Paducah, KY: American Quilter’s Society, 1998).

“18th Century Printed Cotton Fabrics,” http://demodecouture.com/cotton/