|

| Advertisement from the Plattsburgh Sentinel |

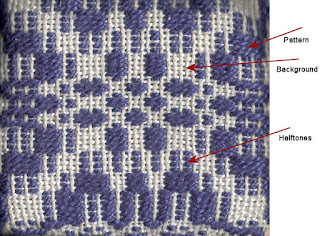

On the fifth day of Redpath’s stint in Plattsburgh, August 19, Anna Ernberg gave a lecture and demonstration of dyeing, weaving, and handcraft. The advertising in the Plattsburgh Sentinel gave no further information about Ernberg, perhaps assuming that audiences would be familiar with her. As the head of Fireside Industries at Berea College in Berea, Kentucky, Anna Ernberg was one of the most visible proponents of the Appalachian weaving revival in the early 20th century.

|

| Coverlet given to Alice Miner by Anna Ernberg |

|

| Anna Ernberg weaving on the small counterbalance loom she designed and introduced to Berea, 1912 |

Ernberg directed Fireside Industries for 25 years and turned it into a reliable source of income for the college. When William G. Frost became president in 1892, he introduced the free tuition policy that continues today. Students needed to work to contribute to their tuition as well as room and board expenses. He also had learned that coverlets were an excellent promotional tool and were much appreciated as gifts to donors. Selling woven textiles would make money for the school and would become central to the school’s public image.

|

| From the Berea Quarterly, 1912 |

|

| An example of the way Berea emphasized the links between “southern highlanders” and early colonists |

In an article on coverlet weaving in the south that appeared in House Beautiful, author Mabel Tuke Priestman praised the domestic weaving revival for being “a very important step in the labor movement, as it gives employment to those living in rural districts, who have few interests in their monotonous lives, and saves from oblivion a beautiful craft, distinctly American in its conception.” Anna Ernberg and Alice Miner certainly would have agreed with this sentiment (whether weavers themselves had the same ideas about their “monotonous” lives is another question). Woven coverlets represented all that was good about the past—diligent work, self-sufficiency, thrift—in a form that was aesthetically pleasing. By bringing these pieces into the modern home, collectors hoped to transmit some of the values associated with them into the present day.

Sources:

If you are interested in learning more about the Appalachian weaving revival, Weavers of the Southern Highlands by Philis Alvic is an excellent place to start. For an earlier assessment of the craft revival, try Allen H. Eaton’s Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands, originally published in 1937. Appalachia on Our Mind by Henry D. Shapiro is the classic work on the place of the mountain South in American consciousness. In All That Is Native and Fine, David E. Whisnant examines how the “cultural missionaries” who came to Appalachia created their own version of folk culture.