|

| A mid-19th c. doll from the Alice’s collection |

This subject first came to my attention through a post on the blog JSTOR Daily, which references a recent article by historian Joseph Wachelder. He examined issues of the London daily newspaper The Morning Chronicle from 1800 to 1827, and found a steady increase in advertisements for presents suitable for giving to children at Christmas. Many of these were toys with educational components, such as chemistry sets, “dissected maps” (geography puzzles), and games based on history and current events.

|

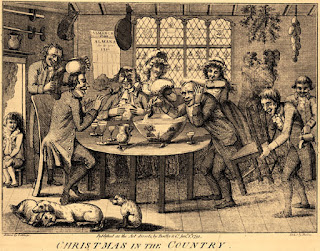

| A scene of Christmas revelry from 1791 |

But gradually, over the course of the 19th century, Christmas became a domestic, family-oriented holiday. Historian Stephen Nissenbaum has argued (in his book The Battle for Christmas) that this change can be traced to the spread of wage labor and capitalist modes of production. For some urban workers, Christmas was just another day of work (think Bob Cratchit). For others, winter might well be a time of unemployment, as water-powered factories shut down until the spring thaw. “December’s leisure thus meant not relatively plenty but forced unemployment and want. The Christmas season, with its carnival traditions of wassail, misrule, and callithumpian ‘street theater,’ could easily become a vehicle of social protest, an instrument to express powerful ethnic or class resentments.”

|

| A child-centered Victorian Christmas |

|

| Portrait of the Edgeworth family by Adam Buck, 1787. As the second oldest of a family of 22(!), Maria had plenty of experience with children. |

|

| A Chinese Puzzle, one of the toys advertised in the Morning Chronicle, 1817 |

Over time, more and more toys would be available for purchase, thanks to technological developments and the continuing sentimentalization of childhood. By the second half of the 19th century, it was difficult for many people to imagine a Christmas that didn’t include toys. So as you’re out searching for Hatchimals this holiday season, remember that you are participating in a tradition that stretches back 200 years!

Sources:

Joseph Wachelder, “Toys, Christmas Gifts, and Consumption Culture in London’s Morning Chronicle, 1800-1827,” Icon Vol. 19, Special Issue Playing with Technology: Sports and Leisure (2013), pp. 13-32

Stephen Nissenbaum, The Battle for Christmas: A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday (Vintage, 1997)

Maria Edgeworth and Richard Lovell Edgeworth, Practical Education (First American edition, 1801)