|

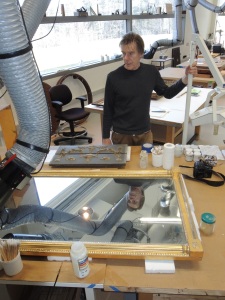

| Portrait of Robert W. de Forest from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum |

The Hudson-Fulton Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum was due largely to the work of two administrators, trustee Robert de Forest and his assistant, Henry Watson Kent. They planned the exhibit to correspond with events that were happening all over New York to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s exploration of the Hudson River as well as the (slightly belated) centennial of the launch of Robert Fulton’s first steamboat in 1807. De Forest and Kent hoped to capitalize on the excitement generated by the celebration, as well as a planned exhibit of Dutch master paintings at the Met, to draw visitors to the American decorative arts display.

|

| Promotional brochure produced by the New York Central Railroad |

Most of the seventeenth-century pieces on display were owned by a single collector, H. Eugene Bolles, a somewhat eccentric Bostonian lawyer who began collecting American antiques long before it became fashionable to do so. His cousin, George Palmer, lent many pieces from his collection of eighteenth-century furniture, while R. T. H. Halsey lent items from his collection of furniture made by Duncan Phyfe in the early nineteenth century. Other collectors lent portraits, silver, ceramics, and pewter, in addition to furniture.

|

| Late-17th century chest with drawers from the H. Eugene Bolles collection |

However, the exhibition also made museum curators realize that some changes needed to be made to the way the items were displayed. At the Hudson-Fulton Exhibition, the furniture pieces were lined up in chronological order along the walls of the galleries. This method of organization was in accordance with accepted curatorial practice, but was thought by some observers to be a bit dull. Moreover, the relatively small scale of the pieces meant that they looked inconspicuous and out of place in the soaring Beaux-Arts galleries of the Met.

|

| View of the Hudson-Fulton Exhibition. Note architectural wall fragment at far right. |

Over the next fifteen years, Robert de Forest and Henry Kent, along with curator R. T. H. Halsey, would work to build the Met’s collection of American decorative arts and to create a proper setting for their display. By the time the American Wing opened in 1924, much had changed in the world of art and antiques—and the colonial revival was about to become more popular than ever.