|

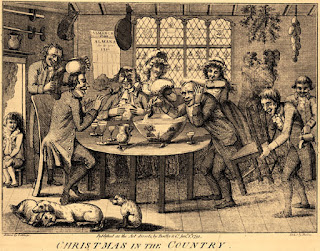

| No “Christmas Gambols” would be complete without a bowl of punch (1783) |

Punch itself has its origins in India, and its first mention in European historical sources comes in a letter from one English East India merchant to another, written in 1632. From India it spread, via merchants and sailors, to the Caribbean, and on to the eastern seaboard of America and to Europe. There is some speculation that the word “punch” derives from the Hindi word panch, meaning five, for the five ingredients, but many punches have more or fewer ingredients.

|

| Majolica punch bowl by George Jones, ca. 1875 Mr. Punch supports an orange-rind bowl |

|

| Scrooge and Bob Cratchit Illustration by John Leech (1843) |

“To make three pints, take a strong, common basin (which may be broken, in case of accident, without damage to the owner’s peace or pocket) and in it place the finely sliced rinds of three lemons, a double-handful of sugar lumps, a pint of dark rum and a large wine glass of brandy. Set alight and allow to burn for three or four minutes (extinguish by covering with a lid). Add the juice of three lemons and a quart of boiling water. Stir, cover, leave for five minutes and stir again. Taste and sweeten if necessary, but observe that it will be a little sweeter presently. Pour into an ovenproof jug or bowl and cover with a leather cloth. Place in a hot oven for 10 minutes. Remove the lemon rind before serving.”

In the American colonies, punch developed in its own way, eventually producing that classic Christmas drink, eggnog. Egg punch was common in Britain, but the Americans made it richer and more custard-like. One observer in 1815 noted that in “the South it is almost indispensible at Christmas time, and at the North it is a favourite at all seasons.” George Washington’s recipe for eggnog included rye whiskey, Jamaican rum, sherry, eggs, sugar, cream, and milk. Eggs and milk were harder to come by in the winter, and more expensive, so eggnog was a true holiday treat.

|

| Pressed glass miniature punch bowl and cups, probably late 19th century |

This post is largely drawn from the site A History of the World Through a Bowl of Punch, particularly the post “Celebrating Christmas and New Year with Punch.” This blog holds a wealth of information about punch, including recipes!